Ol' Pals

Cisco's Legacy

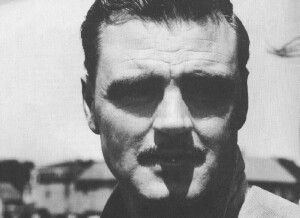

Lee Hays

From Sing Out! Magazine (Oct.-Nov. 1961)

It is not given to every man to know the manner and time of his dying. Cisco Houston knew, and he was glad to know. For, knowing how much time he had left, he found time to do things he had never had time for. He wrote songs. He visited old friends and looked up old buddies he had not seen for years. He wrote letters. He spoke into a microphone hours of memories, reminiscences about Woody Guthrie, Huddie Ledbetter (Leadbelly), his family, his boyhood days in the California depression, the story of his service in the U.S. Merchant Marine (in World War II), his days as a union organizer, his trip to India for the U.S. Department of State; opinions about the world and politics; his estimate of friends, individuals and folksong magazines, and his views of life and death.

He kept working almost to the end of his days, and when his pain cut him down and he could not work, he talked with visitors and prepared jokes to pull on them. In a last telephone talk, only hours before he died, he was able to give messages to friends: "Just remember I love you all." And he was able to joke about death itself: "The trouble with my whole life has been that my timing is always bad." So, as he lay dying, one of his songs was moving up on the pop song charts and he was able to joke with his friend and business partner Harold Leventhal, about the extra Cadillacs he was going to buy with the proceeds. His new Vanguard recording of Woody Guthrie songs was receiving warm notices and was beginning to emerge as the most important recording he had ever done.

The last time he went out, he went to a folk song concert in Pasadena. He wanted to go, saying, "I've heard every damn song, but what the hell, might as well hear them one more time." He was in pain, and did not stay for the encores, and he apologized to the singers before leaving. Before he left New York he worked at Gerde's Folk City, where several of his performances were recorded. He went to Vanguard for extra recording sessions, and the result will be two final longplaying records of song and talk.

(Typist's note: As far as I can tell, the two additional LP's never happened. The taped memories Lee got him to record were material for a planned biography of him by Mr. Hays, but that never got finished either, partly due to Hays' own serious health troubles.-- Bill Adams)

Cisco read poetry, marking passages that he liked. He liked Robert Frost:

The woods are lovely, dark and deep

But I have promises to keep

And miles to go before I sleep.

And Walt Whitman:

Whether I come into my own today, or in ten thousand years

I can cheerfully take it now--with equal cheerfulness, I can wait.

After an afternoon session of talking his memories onto tape, young singers would come to dinner. He would turn the machine on to record his conversations with them. He gave advice. He kidded, but he wanted to share all he had learned. He felt he had been fortunate, with other members of his Depression generation, in being educated through living in hard times and struggle. He tried to tell the young people to join things, to study, to do what they could do to overcome the evils of "Jim Crow" race prejudice, nuclear fall-out, apathy and dishonesty. To a guitar picker aged 13 he said: "Don't goof off like me. Play the guitar now, study it, if only a few moments each day. When you get to be 20, you'll have something to be proud of." To a young folksinger who wanted to leave school and bum around the country Cisco said: "Sure, see the country. But put first things first. You don't have to go on the road just because Woody and I and Pete and Lee did it. We HAD to. Everybody wants to live well. That's what we're fighting for. Fight for education and clean clothes, and stay away from railroads!" (As to Cisco's claim that he was a poor guitar picker: he played, at Gerde's Folk City and at the Vanguard recording studio, rhythms, licks, styles and varieties on the guitar that no one had heard him do before. One friend allowed that Cisco now had time to try for effects that he had never attempted before.)

His words on tape are being transcribed, and may become a book. Some of his stories, with his great hearty laugh and the joy he felt, will be heard someday on records. To hear Cisco talk is a strange experience. He is alive on tape, and more alive than some of those who listen to it. Before he left the East, Cisco went to see Woody Guthrie in his hospital. He said later "It just breaks my heart to look at the guy. Woody faces all this with tremendous courage. If I were placed in that position, having to struggle on for years and years, I don't know how good I'd be at it. If you know my own situation, which is a matter of weeks, or months at the outside before the wheel runs off...well, nobody likes to run out of time. But it's not nearly the tragedy of Hiroshima or the millions of people blown to hell in war that could have been avoided. Those are the real tragedies. It's better to know. It's a real privilege to know that you've only got so much time. Other than that, you know, it's a few more winters wishing it were spring, or a few more summers wishing they would last."

Cisco touched people. People who knew him for only an hour grieve, and are strangely comforted, remembering how Cisco touched them. He knew his own imperfections better than anyone. But he walked with grace through an imperfect world, and the world will be better because of the lives he touched. Through his work, and especially that part of it which he achieved in his last days, when he was in pain, he will continue to touch and move people for time and time to come.

Note: both pictures accompany the article in the magazine. Click on them for a larger version of the image.

We welcome any suggestions, contributions, or questions. You send it, we'll consider using it. Help us spread the word. And the music. And thanks for visiting.